News

St Bart’s Pathology Museum: A Potted History

The medical student walks reverently across the parquet floor: hanging gas lamps spill pools of light onto the polished wood, and as his shadow swims through them he hears the echoes of his footfalls rise purposefully to the lantern ceiling.

The medical student walks reverently across the parquet floor: hanging gas lamps spill pools of light onto the polished wood, and as his shadow swims through them he hears the echoes of his footfalls rise purposefully to the lantern ceiling.

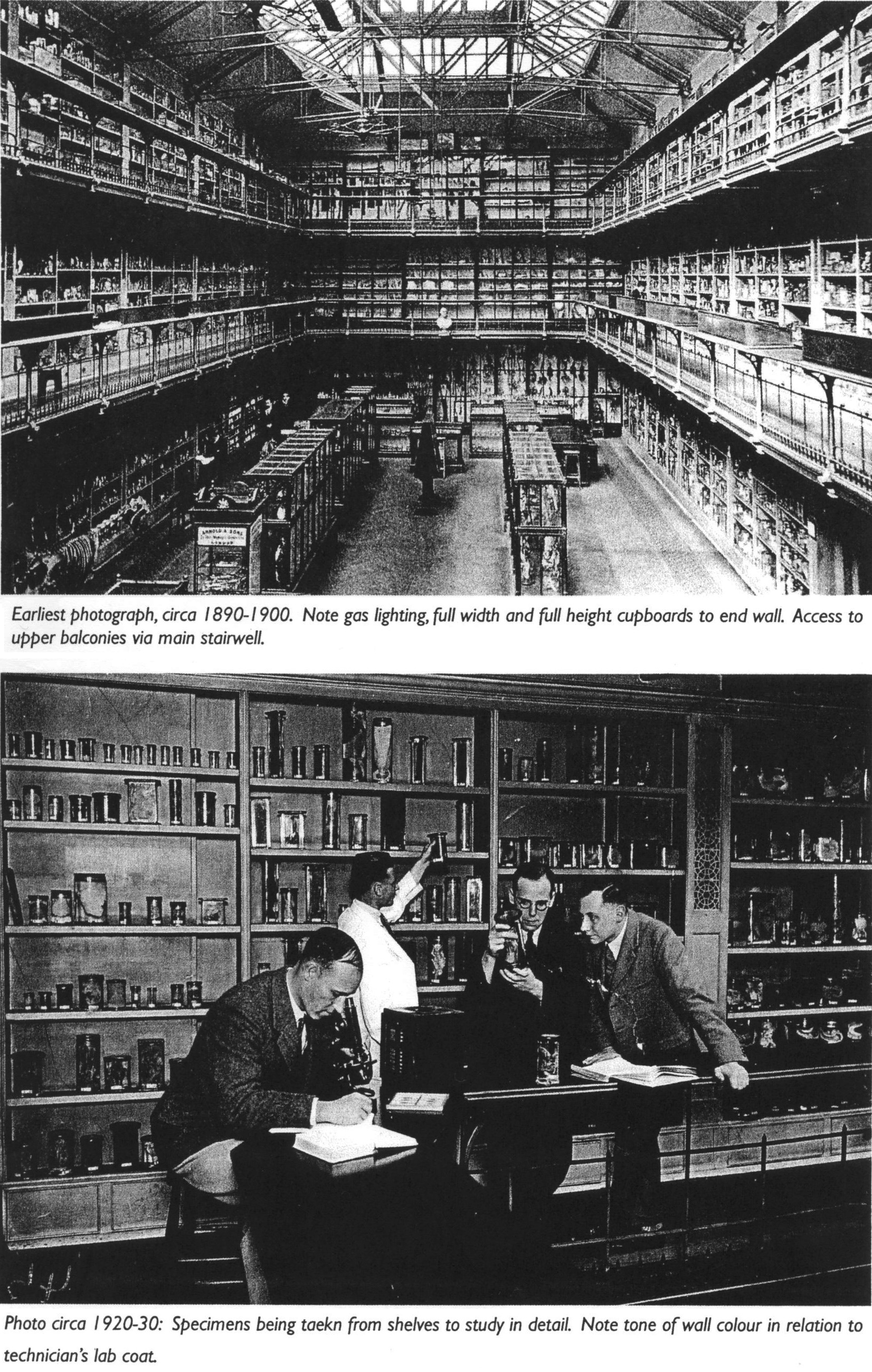

He passes shelf after shelf of potted specimens, golden light bouncing from the curved glass like wolves eyes in the moonlight, until at last he locates the pot he is seeking. Carefully he picks it up and examines the delicate minutiae of the specimen, recording each detail deftly with his pencil, softly scratching the paper with the lead, the quick strokes the only sound in this silent, cavernous museum…

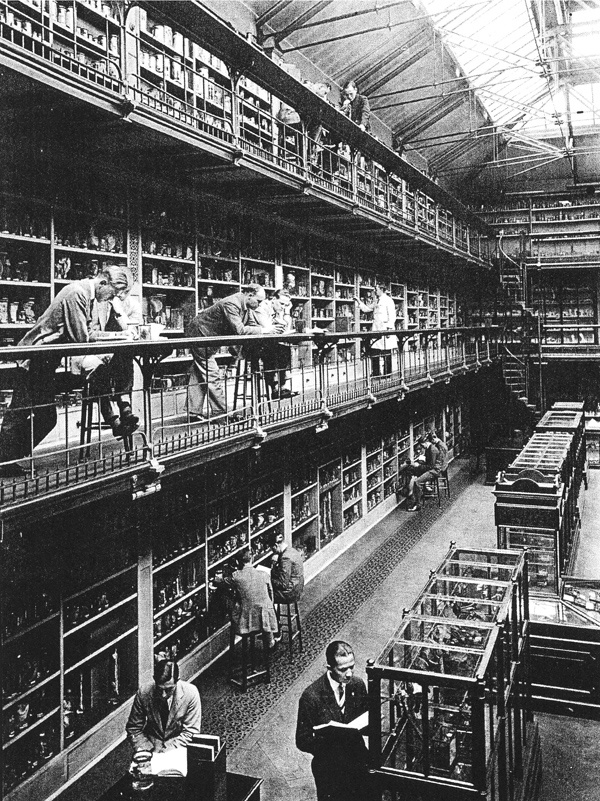

The way we teach medical students may have changed since the heyday of the Pathology Museum in the 1920’s and 1930’s, but the building itself has lost none of the drama. The architect Edward I’Anson oversaw the completion of the museum in 1878 and it was opened in 1879 by Edward VII. Although built in a similar style to many other medical museums of the era, it differs in that it is an open plan space of approximately 28x11 metres square. It is made up of 3 mezzanine levels each around 8 metres high, all linked by a beautiful spiral staircase. After an illustrious history helping along the careers of such famous names as James Paget, Percival Pott and his student John Hunter among others, the museum was awarded Grade II Listed status in 1972. However, after the opening of a new Pathology department in 1909 and an extension for Clinical Skills teaching being built in the 1970’s, the old Pathology Museum gradually fell into disrepair. This neglect seems absolutely criminal when considering that these shelves house specimens such as the skull of John Bellingham (the assassin of the Prime Minister, Spencer Percival) who was subsequently 'hanged and anatomized' for his crime in 1812. The infrastructure began to suffer, as did the collection itself, and it has taken many years of grant applications and cajoling of trustees for the management to be able to fund a technician to conserve the specimens and breathe life into this grand but crumbling relic.

The way we teach medical students may have changed since the heyday of the Pathology Museum in the 1920’s and 1930’s, but the building itself has lost none of the drama. The architect Edward I’Anson oversaw the completion of the museum in 1878 and it was opened in 1879 by Edward VII. Although built in a similar style to many other medical museums of the era, it differs in that it is an open plan space of approximately 28x11 metres square. It is made up of 3 mezzanine levels each around 8 metres high, all linked by a beautiful spiral staircase. After an illustrious history helping along the careers of such famous names as James Paget, Percival Pott and his student John Hunter among others, the museum was awarded Grade II Listed status in 1972. However, after the opening of a new Pathology department in 1909 and an extension for Clinical Skills teaching being built in the 1970’s, the old Pathology Museum gradually fell into disrepair. This neglect seems absolutely criminal when considering that these shelves house specimens such as the skull of John Bellingham (the assassin of the Prime Minister, Spencer Percival) who was subsequently 'hanged and anatomized' for his crime in 1812. The infrastructure began to suffer, as did the collection itself, and it has taken many years of grant applications and cajoling of trustees for the management to be able to fund a technician to conserve the specimens and breathe life into this grand but crumbling relic.

I was lucky enough to be that technician, and the project has so far been the most interesting and satisfying one I’ve had the honour of being involved in. The place itself is fascinating, as are the specimens held within, and there is an interesting history attached to nearly every object. For example, Bart’s Hospital is the place Sir Arthur Conan Doyle chose for his characters Holmes and Watson to have their first fortuitous meeting. There was even a plaque commemorating the event on my office wall that had been there since the 1950’s. As a result, I have now been given honorary membership of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London and the organisation will show film screenings here in the future. That is one of the benefits of the open plan space: not only do we have room for AV

equipment and seating, but there is even room for a bar! We held a very popular seminar series before Christmas and are planning a second one for spring with each seminar offering free wine and CPD credits. Recently we were fortunate enough to have been approached by different aspects of the media enquiring about writing articles and filming footage here for documentaries: we've been host to the BBC, The Guardian Newspaper and members of Time Team.

equipment and seating, but there is even room for a bar! We held a very popular seminar series before Christmas and are planning a second one for spring with each seminar offering free wine and CPD credits. Recently we were fortunate enough to have been approached by different aspects of the media enquiring about writing articles and filming footage here for documentaries: we've been host to the BBC, The Guardian Newspaper and members of Time Team.

However, the most exciting development for 2012 involves our sister gallery space at The Royal London Hospital which houses the famous Joseph Merrick or 'Elephant Man', who suffered it is believed, from Proteus syndrome. Due to his family’s requests, the skeleton itself can’t be moved from the gallery in Whitechapel. However, a very famous Hollywood actor visited him after hours last year and kindly offered to pay for a replica of the skeleton to be made. The offer subsequently grew to a full scale refurbishment of the gallery at Whitechapel too, which happens to coincide with the 150th Anniversary of Merrick’s birth. These offers are exciting and allow us to consider a number of options on how best to provide an educational display on Proteus syndrome.

Similarly, the conservation of our specimens here at West Smithfield will enable us to create a similar lay-out to that of the Berlin Medical History Museum in which only the ground floor gallery is open to the public and contains the interesting historical specimens, with the upper galleries reserved solely for teaching and for allied health professionals (such as APT’s).

With an entry in the English Heritage handbook due in June (which will list us as one of London's "Hidden Treasures") the establishment of a historical display of specimens, the construction of a new website and the increasing media involvement, 2012 looks to be an exciting year for St Bart’s Pathology Museum.

(We are not yet open to the public but for private viewings contact Carla Connolly on c.connolly@qmul.ac.uk or call 0207 882 8766. The upcoming seminar series will be advertised on the AAPTUK website)

Carla Connolly