News

Morning Report from the Annual Educational Event 2024

Jennifer Williamson MAAPT reports on her experience of the morrning session at AEE 2024

On September 28, 2024, the 20th Annual Education Event for the Association of Anatomical Pathology Technology took place at the Village Hotel in sunny Glasgow.

This was my fourth time attending, and I always look forward to reconnecting with familiar faces and meeting new colleagues.

Since the event was held in Glasgow, which is closer to home for me, I was lucky to attend with a group of colleagues from NHS Lothian and the City of Edinburgh Council, some of whom were experiencing the AEE for the first time. I was excited to share this day with them. As always, the AEE provided an excellent opportunity for APTs to network, meet representatives from various companies, and hear inspiring talks on unfamiliar topics—this year was no exception.

After registration, we enjoyed coffee and delicious pastries before exploring the commercial exhibits, which showcased the latest mortuary equipment and products. The morning began with an introduction from Robert Cast, Mortuary Service Operations Manager at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, who emphasized the importance of confidentiality and consideration for fellow attendees.

John Pitchers, AAPT Chair, then welcomed us to AEE 2024, highlighting this year’s impressive program and a minor change to the schedule.

The first presentation was by Professor Michael Osborn, AAPT President from Imperial College, who discussed Fire and water deaths. Drawing from his experience as a histopathologist at St Mary’s Hospital and Westminster in London, he covered the protocols for investigating deaths in these contexts. Fire deaths are uncommon, occurring only once or twice a year.

However, with the River Thames running through London, it is also home to the busiest Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) station in the country, which responds to approximately 400 drowning deaths annually in England.

Given my hospital background, I have limited experience with these types of cases, having encountered a drowning only once during my training, so I was eager to expand my understanding. Prof. Osborn stressed the importance of gathering the events history and context and ruling out other potential causes of death, such as whether the person was deceased before entering the water or before a fire started. He examined injury patterns and post-mortem examination techniques, including how to determine burn sizes.

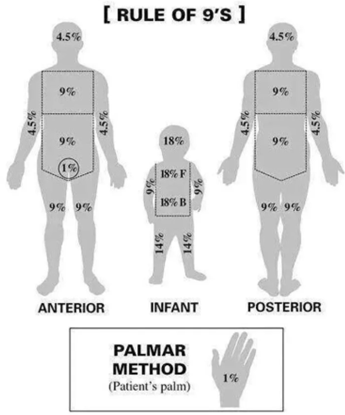

I learned about the "RULE OF NINES," a method for estimating burn size by dividing the body’s surface area into percentages. Additionally, the PALMER METHOD was also introduced as a simple way to estimate total body surface area (TBSA), where the palmar surface of the patient's hand equals 1% TBSA.

Next, Prof. Osborn addressed drowning and submersion deaths, noting that not all submersion incidents result from drowning; some may be due to neurological responses when entering water, I was particularly interest to learn that this particularly occurs during emotional or stressful situations. He pointed out that proving drowning at autopsy can be challenging since the presence of water in the lungs isn’t always definitive. The process often involves exclusion, concluding drowning only when no other significant causes are found.

I was particularly intrigued by the use of diatoms in drowning cases. Having attended a previous AAPT webinar on diatom analysis by Dr. Kirstie Scott, I was fascinated by these tiny organisms’ roles in forensic science. Prof. Osborn explained that diatoms are ubiquitous and can enter the bloodstream, potentially being found in various organs.

He described an experiment in which dogs were fed prawn sandwiches to demonstrate that diatoms can cross the gastrointestinal barrier and enter other areas of the body. A similar process occurs in drowning cases, where diatoms can enter the bloodstream and potentially be found in the bone marrow and other internal organs, such as the spleen. This realisation certainly impacts my meal choices!

The second presentation was Denmark: How (paper)work is done by Christian Hyldager MAAPT from the Retsmedicinsk Institut in Denmark. He thanked Simon from Chemsol for recommending him and provided an insightful and humorous overview of how his international colleagues work. Christian explained that their institute operates independently from police and hospitals, ensuring impartiality in investigations.

They follow distinct pathways for conducting post-mortem examinations. One key difference is that forensic post-mortems typically require family consent. If the family does not consent but the examination is deemed essential, legal action may be taken to obtain an order. This contrasts with Scotland, where families have no authority over the type of examination performed in forensic or procurator fiscal cases.

Christian also described the unique logistics of traveling to remote areas like Greenland and the Faroe Islands for autopsies, often using boats or helicopters to reach the most rural areas. When asked why the post mortem service hasn’t been centralise to the larger facility in Copenhagen, Christian and Henrik, Retsmedicinsk Institut Operation Manager, explained this was for the dignity and respect for the bereaved family and the deceased.

I found it fascinating to learn about the various departments and specialisations among the staff, from DVI specialists to those in training and general ‘bob the builder’ roles. Christian described his role as the biobank manager, highlighting how demanding it became during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a significant increase in workload due to the 70 specimens collected from 200 cases.

He then detailed their setup and facilities, which include four large cooling rooms, a radiology suite with MRI and CT machines, four autopsy rooms, and a beautifully designed viewing area and chapel that comfortably accommodates 40 people. This was a striking contrast to the facilities I have encountered before. It was an insightful and enlightening presentation about these differences, and I think we all felt a bit envious of their setup—especially the cleaning staff!

After a brief coffee and tea break, we had another chance to explore the commercial exhibition before moving on to the abstract presentations. The first abstract was delivered by Meritxell (Mary) Miret Gonzalez MAAPT, mortuary service manager at the Royal Free Hospital London. Her presentation, titled Care After Death Guardians: How APTs Can Educate Others focused on her work in training staff on various aspects of post-death care. She also discussed her role in developing a training program for Care of Deceased Guardians within her health board.

Mary and her team identified areas with increased reportable incidents, such as patient damage, inappropriate dressing, and information discrepancies, and tailored training to address these issues. Since 2021, Mary has conducted over 60 sessions, engaging more than 500 staff members through short refresher courses and more intensive simulation days. She emphasized that "Death is a part of life," a sentiment I strongly resonate with. Through this training, the multidisciplinary team has been able to visit the mortuary, reducing fears and stigma surrounding death.

I found this session particularly valuable, as I am responsible for training in my health board, but we have yet to establish a formal course or competency tracking system. I believe the introduction of "Care After Death Grab Bags" is an innovative resource for staff. These prefilled bags contain all necessary items for post-death care—such as body bags, shrouds, and documentation—saving time and proving useful in the wards.

The training's impact is evident from overwhelmingly positive feedback from the pilot program, which has resulted in a 50% annual reduction in care after death incidents since its implementation. Mary’s abstract presented some fantastic ideas that clearly demonstrate the importance of mortuary engagement and help break down barriers and taboos surrounding death.

The second abstract, What does it mean to respect the dead? presented by Dr. Imogen Jones and John Pitchers FAAPT, sparking a thought-provoking discussion about our understanding of respect. Special mention goes to Imogen’s animations throughout the presentation and the use of questionnaires, which provided a valuable platform for real-time feedback on the topics addressed.

Their exploration of what 'respect' entails led us to examine the distinctions between respect and dignity. Imogen and John highlighted how both terms are referenced in regulations relevant to our daily work. For instance, human tissue regulations mention 'respect' 25 times and 'dignity' 30 times, yet they fail to define the critical shortcomings in these areas. In contrast, the Royal College of Pathologists refers to 'dignity' only once, while the AAPT doesn’t mention either term in any strategy.

This discussion revealed that we often associate these concepts with negative connotations, focusing on what is deemed undignified or disrespectful, from the quality of care to the language used.

They engaged the group in a thinking exercise, presenting scenarios for attendees to respond to via their phones. The questions included:

- How do we refer to deceased individuals who are bariatric or decomposed?

- Do we label them as 'large patients' or 'the decomp' instead of using their names?

- Should we view individuals as a risk for infection based on their lifestyle choices, leading to potential stereotyping?

- When using dignity garments to cover a deceased person's genitals, what happens if these become soiled?

- Does this respect the deceased's cultural or religious beliefs?

- Would the deceased care about being naked, or is this more about the staff's need for modesty?

This exercise facilitated an open discussion on familiar yet sensitive topics, allowing for an exploration of diverse viewpoints and emotions. I look forward to the report on this feedback and continuation of this conversation.

The final presentation of the morning was delivered by Dr. Mark Gregson Lord, focusing on the topic of Medical Murder?. Mark reflected on his experiences as a general pathologist serving as an HM Coroner and Procurator Fiscal pathologist, sharing several intriguing cases from his career.

He presented five case studies involving patients of various demographics and ages, offering insights into the circumstances leading to each death and the medical oversights that contributed to them.

The two cases that resonated with me the most involved a 45-year-old man who visited his local accident and emergency department with a sore leg and shortness of breath. He was discharged after being diagnosed with a panic attack, a condition that the health board knew he had had previous admissions for. The following day, he was found collapsed and unresponsive, ultimately dying from deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The second case involved an 82-year-old woman who died from septic arthritis following a recent knee replacement.

This case particularly struck me because a doctor has diagnosed the patient with this early in the day, but due to the surgeon’s refusal to acknowledge that the surgery could have caused an infection, it resulted in delayed treatment resulting to her death.

I was surprised to learn that in four out of five cases, arrests were made for gross negligence manslaughter, yet none went to court, resulting in local hospital policy changes. This was a truly eye-opening presentation regarding the state of care within our health boards and the implications of malpractice.

Once again, we were treated to fantastic talks covering various aspects of our profession, showcasing the knowledge and care being provided across the UK and beyond. I’d like to extend my thanks to the speakers, the morning chair, and the commercial representatives for making the AEE such an excellent event. I look forward to next year’s AEE in Bristol!